The international evidence shows that PPI is feasible, but evidence on the economic costs of PPI in research is sparse . It shows that drawing on the lived experience of PPI contributors can have positive benefits for health and social care research. It can lead to better outputs , and while it can enhance the quality and relevance of studies the evidence base on its impact remains weak.

There is evidence that PPI in health research can become tokenistic and concern that inviting patients and the public to ‘tinker at the edges’ undermines the broader aim of PPI to democratise research . International evidence shows that researchers are willing to change their practice, but lack of knowledge, skills and experience can hinder their involvement in PPI and they may be apprehensive about using PPI.

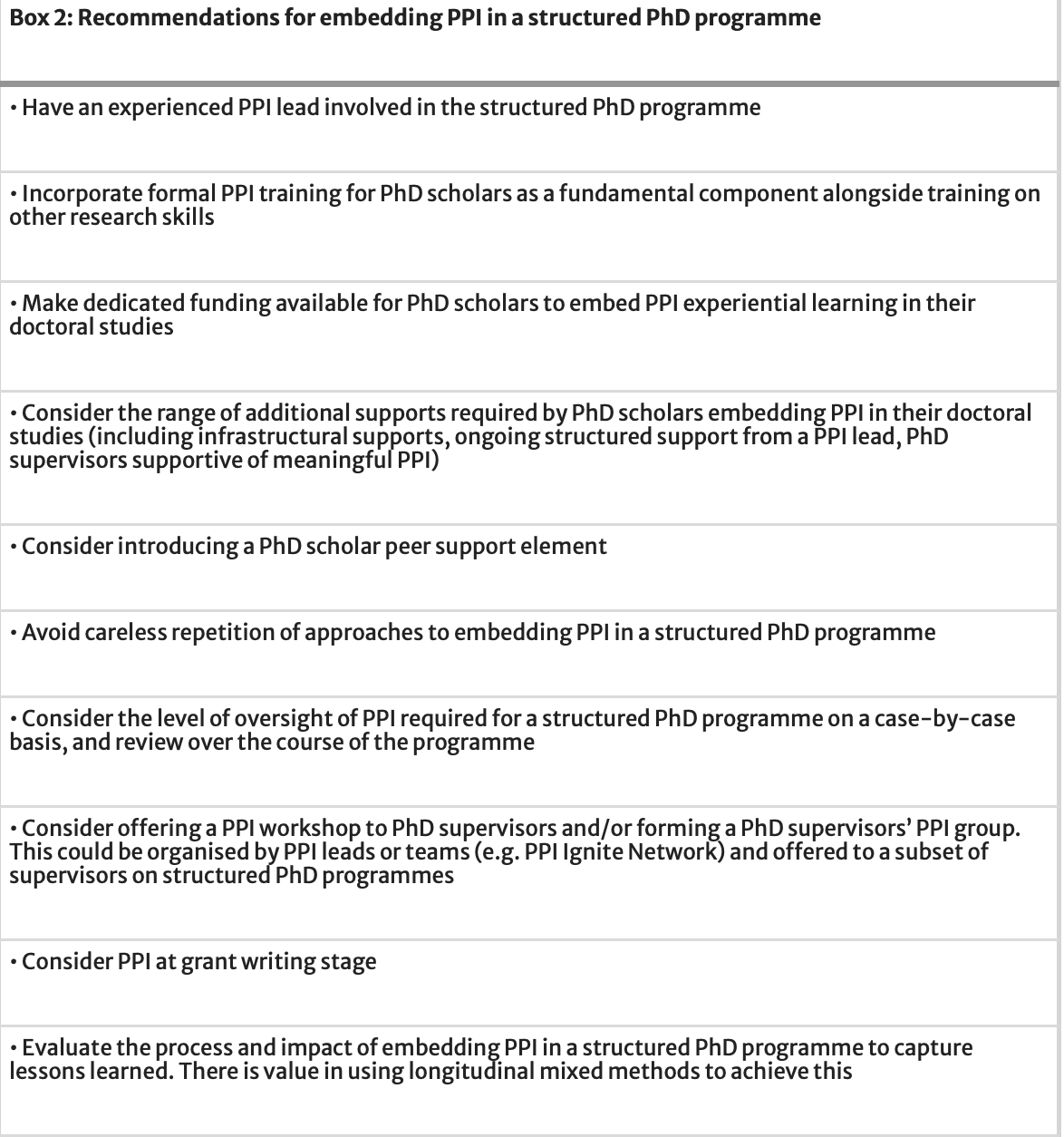

Conclusions

Embedding formal and experiential PPI training in a structured PhD programme is a novel approach. The evaluation has identified a number of lessons that can inform future doctoral programmes seeking to embed formal and experiential PPI training.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40900-023-00516-4